2025 Summer Wrapup

When it comes to our home gardening, the summer of 2025 will go down as a great year for growing veggies and producing cultivated mushrooms. Over the last few years, Sandy and I have been spreading wine cap (Stropharia rugosoannulata) spawn all around our backyard. We mix the spawn with chopped garden straw and a blend of aged hardwood and conifer chips. It’s important that the straw you use hasn’t been sprayed with Roundup or any other toxic chemicals. If you inoculate an area during the summer or early fall, you will most likely start seeing wine cap mushrooms the next spring. We’ve had wine cap flushes in the past, but this summer they occurred more frequently and in greater numbers. The ones that fruited during warmer days and nights looked normal, but those in the early spring manifested some odd characteristics.

The mushrooms in the top half of this composite picture display normal cap structures, whereas those below do not. Mushrooms that exhibit this cracked-cap pattern are referred to in Asian countries as “Donko”. In Japan, Donko can refer to the cracked-cap shiitake mushroom or a species of sleeper goby fish. In China, it translates to “winter mushroom”. In both countries, Donko mushrooms are highly sought after due to their concentrated flavor. The cracked cap is a result of cold nights and warmer days. These dramatic temperature swings along with inconsistent moisture results in a kind of stop-and-go growth pattern. At night, when temperatures are cold, there is virtually no cap expansion.

During the warmer daytime, the mushroom’s cap stretches and cracks to make room for the expanding tissue beneath its surface, thereby creating the white fissures. Our crack capped wine caps had a texture similar to partially dehydrated mushrooms. I can’t attest to them having concentrated flavor, but they were perfectly edible and kind of cool looking. Unlike in Japan, with their highly prized and more expensive Shiitake Donko mushrooms, I certainly wouldn’t have paid more for our Donko wine cap.

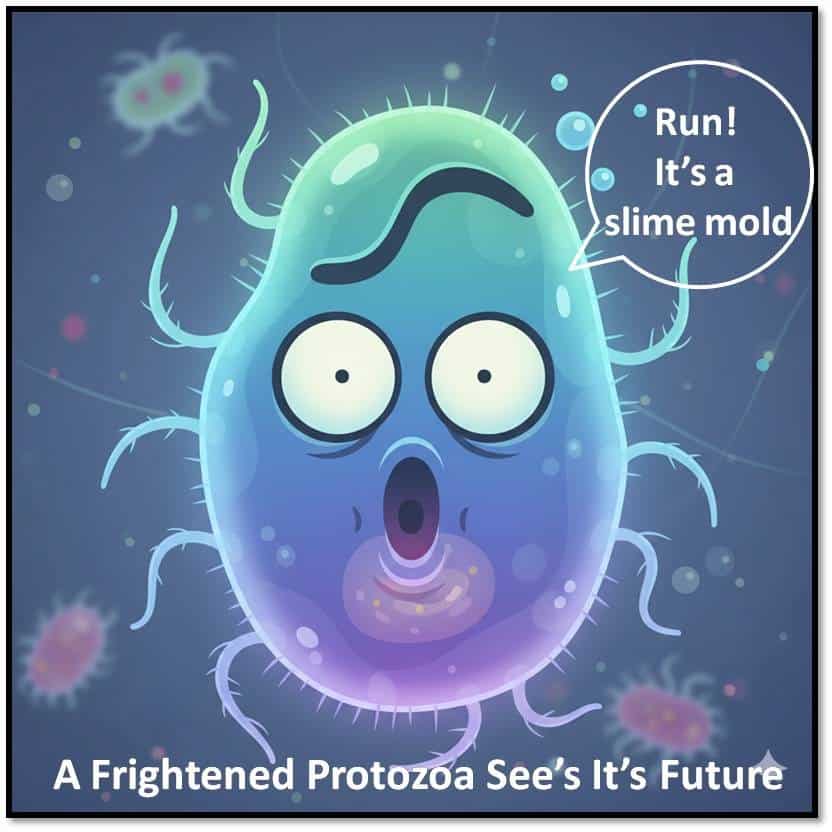

Besides wine caps, oysters, and shiitake mushrooms that graced our summer garden, we also encountered an interesting slime mold visitor called Fuligo septica. Prior to the creation of Robert Whittaker’s five Kingdom classification system in 1969, this interesting organism was lumped in with mosses, ferns, algae, fungi, bacteria, and house plants under the Kingdom Plantae (plants). After 1969 and based on its physiology, F. septica was placed into the Kingdom Protista. The Kingdom Protista includes all eukaryotes (organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus) that are not animals, plants, nor fungi.

Simply put, Kingdom Protista seems to be a kind of eukaryote dumping ground for oddball organisms. The Latin name, Fuligo septica, is quite interesting. Fuligo means “soot”, which describes the black, sooty looking cloud of spores it emits at maturity. Septica translates to “rotten” or “putrefying”, referring to the fact that F. septica is found on decaying organic matter such as rotting wood and mulch. Google’s AI-chatbot called Gemini described F. septica’s eating habits this way: “The slime mold’s primary food source is the bacteria, protozoa, and fungi that break down dead organic material. When you see F. septica on wood mulch, a rotting log, or decaying leaf litter, it is not eating the wood itself.

Instead, its single-celled, amoeba-like plasmodium is engulfing the microorganisms that are actively decomposing the material.” Unlike saprotrophic fungi, F. septica lacks the digestive enzymes to directly break down wood and other materials. So, it only makes sense to eat those that do, unless of course you’re a bacterium or protozoan.

F. septica starts out as this very attractive, yellow, sponge-like looking blob. At this early stage of life, it has been commonly referred to as “scrambled eggs”. However, as its food supply runs out, it transforms itself into a crusty looking dark blob. This is its reproductive stage, where it will soon release millions of spores in a sooty cloud of smoke. It is also this stage of life where it gets the unflattering common name of “dog vomit”. While it does look like something that was left behind, it looks more like something from a behind rather than from a mouth.

While there are plenty of spectacular article headings like “Slime Mold Beats Humans at Perfecting Traffic Networks”, my focus was on encouraging them to eat microorganisms in someone else’s yard. I’m not exactly sure how to go about training them to do that, and at times it seems more like they’ve found a way to train us.

Removing them early on seems to have kept their total yard domination in check. Once they start pumping out those big sooty looking clouds of spores, they will start to pop up just about everywhere. I’ve learned not to try to remove them in their very sticky yellow stage. It’s like trying to grab a handful of gooey honey.

Once they darken, they become quite crusty and can more easily be lifted off the surface, microorganisms and all. I don’t dislike this interesting slime mold; I’d just rather not have all that sooty putrefying going on in our garden. By the way, in some parts of Mexico, F. septica is eaten during its young scrambled-eggs stage, before it goes all dog vomit on itself. I think I’ll stick with real eggs.

Otherwise, mushroom season has already begun, and it’s time to hit the woods. As our temperatures cool and rain starts falling, mushrooms start popping up. Areas along the coast and cascades are already experiencing mushroom flushes.

We collected a few lobster mushrooms as well as chanterelles in early September. You may need to hike around several spots to find enough for a meal, but I can’t think of any downside. It may take a little while longer to start seeing boletes, although the Cascade Range does start pretty early. While some years have gone into December before the Cascade Range starts getting killing freezes, it has also happened as early as September.

That said, here is this year’s Cascade Range best weather guess by Axios. ” Weather predictions suggest the Cascade Mountain range will experience a warmer-than-average fall, with temperatures remaining mild and potentially delaying the arrival of typical winter cold until December. This forecast is influenced by a developing La Niña pattern and ongoing long-term climate warming trends.”

I’m not sure how accurate Axios might be, but it does sound like a mushroom friendly prediction. In any event, grab some friends and get out there and reconnect with nature. Maybe try some new mushrooming spots, take lots of pictures, and above all else, stay safe and have fun.

Ron