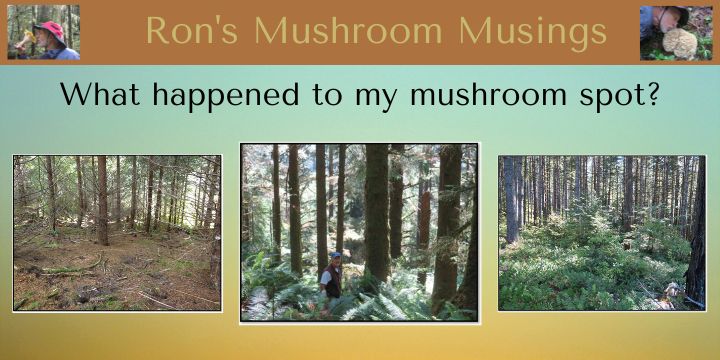

What happened to my mushroom spot?

For Sandy and I, hunting for wild mushrooms in Oregon forests is exciting, good exercise, and just being in and around nature helps rejuvenate one’s soul. After a long and sometimes hot season of gardening, we look forward to the return of fall weather and the start of Oregon’s rainy season. Fall (usually) brings the rain and the rain (usually) encourages mushrooms to start fruiting. Over the years we have put together a nice portfolio of locations where we enjoy hunting for mushrooms. However, the biological makeup of a mushrooming area can quickly change. The state of Oregon ranks number one in the US for timber harvesting, which is done on Private, State and Federally managed land. In Oregon, the federal government owns 61% of forestland, 3% is owned by the state and 34% by private landowners. Logging contracts are issued for both federal and state owned property. Basic logging operations consist primarily of tree thinning and clearcutting. In addition, so far in 2024, forest fires have burned more than 1.9 million acres of timberland. Any one of these events will certainly impact the biology of a forest and subsequently anyone’s mushroom spot.

Sandy and I have encountered and lost mushroom hunting areas due to all of these events. We have also had a great interest in how various mushroom species respond to these disturbances. To find out, we have been monitoring both a 2007 replanted area of Douglas Fir trees on Roseburg Forest Products property and a BLM managed area that had been thinned in 2014. Our mushroom observations have taken place over the past 10 years.

To find out more specific information about the Douglas Fir tree area replanted in 2007, I called and spoke to a representative from Roseburg Forest Products. He was very helpful and gave me information regarding Douglas Fir trees that I was previously unaware of. I was told that newly planted seedling trees put on very little growth during their first few years while they work on reestablishing their root system. Afterwards, depending on location and environmental conditions, they can grow anywhere from 3 to 5 feet in a single growing season.

Roseburg Forest Products also uses proprietary strains of Douglas Fir trees bred for disease resistance, speed of growth and quality of wood. When we first started observing mushroom activity in this replanted area it was already 7 years old. Due to the dense planting of trees, the forest floor was fairly devoid of undergrowth. Standing under the trees, it felt very cool, slightly humid with plenty of ground moisture. There were mosses in some areas, some ferns and a limited amount of organic forest debris. Mushroom fruiting in 2014 was mostly limited to opportunistic saprotrophic mushrooms in the genus Lepiota as well as in Mycena. Other, more typical little brown (or baby) mushrooms (LBM’s) were also sighted. At that time, no mycorrhizal species were observed.

While the species of saprobic fungi increased from year to year, it wasn’t until 2013 that we started seeing our first mycorrhizal species, mainly in Russula and Laccaria. Those first mycorrhizal observations were made 16-years after this area was replanted. One year later in 2024, The mycorrhizal diversity had increased to include species in Lactarius, Suillus, and Cantharellus. More Saprobic fungal species have also sprung up including a stunning patch of Pholiota aurivella.

After 17 years, the mushrooms in this replanted area of proprietary Douglas Fir trees seems to have mostly restored themselves. Whether through natural spore seeding of these fungi and/or restoration from mycelial remnants that survived the clearcut, mushrooms were back. However, I was also told that this area of replanted trees would be assessed around its 25th birthday to determine its disposition going forward. It is in fact a privately owned tree farm with the sole purpose of growing and harvesting trees for lumber. Fortunately, Roseburg Forest Products are magnanimous enough to allow public access to some of their properties as long as people are respectful and considerate. Conversely, some logging companies do not offer such a courtesy.

As for the BLM managed area, I was able to speak with Sarah from the Springfield BLM office. She was also extremely helpful and willing to share her insights and knowledge of this area. And by the way, she’s also a mushroom hunting enthusiast. While thinned in 2014, it still has amazingly large, 80+ year old Douglas Fir trees on it. Planted back in 1944 with Douglas Fir trees, it has been thinned and allowed to naturally repopulate itself with a more diverse population of native trees and understory plants.

As part of a 2016 BLM habitat restoration program, some Douglas Fir forests are being thinned and naturally repopulated for the benefit of wildlife and eco-diversity. Unlike the Roseburg planting, we did have the opportunity to hike around these forested areas prior to thinning. At that time, they hosted a very diverse population of fungi including Chanterelles, Matsutake, and Boletes. Since the thinning, this area has also been going through its own fungal recovery process. And, just how the transition from a Douglas Fir forest to a mixed forest will effect fungal activity has yet to be determined. The one difference with this developing ecosystem is traversing through it is much more difficult. Once thinning allowed the sun to penetrate through to the woodland floor, it became a race among plant species to see who will prevail. The areas we were able to walk around in this year have been very dry, quite warm and void of any mushroom activity. We will try again after heavier rains begin to see if that makes a difference.

Take care and happy mushrooming, Ron