The Body Snatcher Mushroom

Fall is getting closer and with the change of season comes the rains and the rains bring mushrooms. Some mushroom species require quite a bit of moisture to get kick started while others are more easily accommodated by lesser amounts of the wet stuff. The genus Russula is one of those collection of mushroom species whose needs are easy to satisfy and are quick on the fruiting trigger. Whereas some species of mushrooms will not make an appearance until October or later, Russula species can be found as early as August. Yes, that’s this month and yes, they are already popping up as I am typing this article. One of the more interesting species in this genus and sought after for culinary use is the lobster mushroom. Its common name is derived from the reddish color it eventually obtains which is reminiscent of the multi-legged sea creature that bears the same name. However, that’s where the similarities end. This mushroom has neither the texture nor taste of the one living in the ocean. On the other hand, I have seen this mushroom sell for as much as $40 a pound when it first hits our local markets. At that price you are almost better off buying the real lobster, waiting for prices to drop, or better yet, hunting your own for zero dollars a pound.

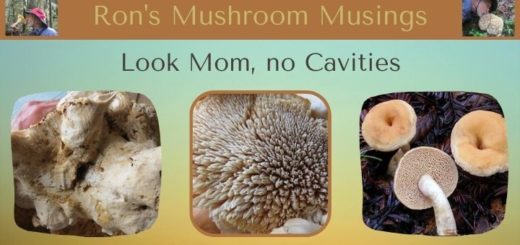

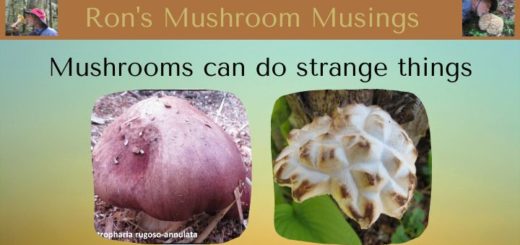

The real oddity with the lobster mushroom is in its humble beginnings. There would be no lobster mushroom without the unassuming and much maligned Russula brevipes. This darling of a mushroom has been the brunt of many a bad witticism as expressed by David Arora in his “All That the Rain Promises and More…” mushroom pocket guide. Listing phrases like “better kicked than picked”, and “better trampled than sampled”. No mushroom should befall such a fate or such negative criticism. Especially when with the aid of a little presto-chango magic it becomes a $40 a pound mushroom. Let’s see David Arora try and get $6,800 for his 170 pound body. So, how does this chalky white mushroom pull off this amazing transformation you ask? Well, I can tell you it’s not a voluntary act or a self-imposed manifestation. Another fungus called Hypomyces lactifluorum drifting in the breeze comes upon the innocent Russula brevipes and begins to engulf it. While some fungi happily play well with others and some decompose dead or dying organic matter, this parasitic fungus attacks the helpless Russula for its own reproductive purposes. A true body snatcher in every sense of the word. Once parasitized, the transformation begins. As Sherlock Holmes would say to Dr. Watson, “the game is afoot”. The white brevipes with its well defined gills and classic mushroom demeanor starts to show signs of structural deformation and color change. Its well defined gills have now taken on a more muted configuration and the cap is becoming ever more contorted as the parasitic fungus continues to fully envelop its host. After several days the transition has been complete and little is left of the original mushroom that only days ago was mostly ignored or seen as just a passing curiosity.

Some might see this as a romantic tragedy or a trick gone completely wrong but it’s just Mother Nature doing its thing. And while I’d like to say that no fungi were harmed during the filming of this article, I would be lying to you. The once stately Russula brevipes has become a $40 a pound super mushroom sought out by many and also found by many. While the Russula brevipes is a fairly easy to identify mushroom, the mutated lobster form of this mushroom is very easy to identify. Although, if the parasitization process begins at a very early stage of brevipes development the lobster form can be quite difficult to see.

Often times only a corner rises above the surface or it takes on so much surface soil and moss that it becomes camouflaged. The good news is if you find one you often times find several more in close proximity. Look for those partially exposed red or orange corners and mounded up areas like something was trying to pop through the soil but never quite made it because some parasitic fungus took it over. However, before you excavate every lobster mushroom you find, remember you will be the one cleaning them and that is neither an easy nor enjoyable task. It may also take you a while and several tries before you find the right way to prepare them to your liking. Do not repeat my mistake and stir-fry them with onions and peppers. The dry brittle texture of the lobster mushrooms flesh (oh, that sounds horrid) will soak up every drop of liquid it can get its chitin covered cells on. The outcome will be a soggy, bad mouth feel, ain’t gonna eat it, mushroom meal gone wrong. A much better method is to cut the lobster mushroom into thin strips, sprinkle it with mesquite seasoning or smoked paprika, and fry it in hot oil until crispy like bacon. Leave the pan uncovered to maximize its crispiness. It will take a while to get just the right texture and doneness, so be patient. Then you can either add the finished product to another dish, make a great mock-bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwich, or just eat it as is. Better still, buy a copy of Cascade Mycological Society’s cook book with tried and true recipes and impress your friends. Just let them know you used a local foraged mushroom if for some reason they may have an issue with that. Always stay safe and good luck with your lobster mushroom foraging.

By the way, if you do not find the lobster mushroom, I have found the Russula brevipes to be quite edible. If you season it well and fry it up crispy you may not even know the difference. Add a little paprika and voilà; you’ve got yourself a lobster mushroom look-a-like without the need for the aid of a parasitic fungus. However, the trick may be to find the right brevipes. According to the book “Mushrooms of the Redwood Coast,” the Russula brevipes group includes 5 variants and describes the edibility like this – “Some forms edible and very good, others downright awful (it is a species complex). Firm young buttons are best, especially those growing with live oak and manzanita.” If you want to harvest the brevipes and try it the best option may be to taste a small piece of the cap before you harvest. You can taste a small portion and spit it out. If it has an acrid taste, do not bother harvesting it. If it is mild tasting, it will more than likely taste mild after cooking.

Short Stemmed Russula (Russula brevipes)

Fruiting period: August through early winter.

Habitat: Solitary to scattered, often in great abundance. Found on the ground in the forest. They are mycorrhizal with a wide variety of trees. In Oregon, they are commonly found near conifers.

Cap: White at first with an inrolled margin, soon dingy white to whitish buff with yellowish brown spots or stains. A centrally depressed cap when small that matures to a vase shape with a wavy uplifted margin.

Spore Surface: Close white gills, decurrent with age; often pale yellow or pale tan in age.

Stem: Thick and solid, mostly equal or a slight tapering towards the base; surface dry white, with yellowish to brownish discolorations in age. The stem of all fresh Russulas “snap” clean like chalk.

Flesh: White and firm when larvae free and young.

Veil/Volva: None

Spore Print: White

Odor: Not distinctive.

Lobster Mushroom (Hypomyces lactifuorum)

According to the book “Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest by Steve Trudell & Joe Ammirati” – “The minute, reddish-orange, flask-shaped fruiting structures of the hypomyces that cover the entire surface of the mushroom can be seen with a hand lens.”

Fruiting period: August through early winter. Early Lobsters are firm and “maggot” free, while those harvested after a lot of rain can get soggy and riddled with worm holes.

Habitat: In the same habitat as the host mushroom – on the ground in the forest, commonly near conifers, often half buried.

Cap: Bright red-orange in color when fully parasitized, slight funnel shape, often contorted with pits and divots.

Spore Surface: Bright red-orange in color, rough and pimply feel. Sometimes with faint blunted ridges where the gills once were.

Stem: Color and texture consistent with spore surface, thick and stout in shape.

Flesh: White and firm when larvae free and young. Modeled with orange in age.

Veil/Volva: None

Spore Print: White

Odor: Not distinctive.

Further reading:

Russula Brevipes – Mushroom Expert

Russula Brevipes – MycoWeb

Hypomyces lactifuorum – Mushroom Expert

Hypomyces lactifuorum – MycoWeb